Gaming has changed. Video games used to be about conquering challenges of varying difficulty in order to reach a goal. Having a solid narrative was often unnecessary or incidental at best. The games were simpler, as were people’s motivations. They wanted to win. They wanted to beat the game, or their friends, for bragging rights and because it was fun. Somewhere down the line this changed – it was no longer enough to win for winnings sake. Gamers needed a reason to play.

It’s hard to gauge exactly when the story became such an integral part of game design. In 1985 it was enough that Princess Toadstool was in another castle. In 1994 it was enough that there was a stolen Metroid, somewhere in the byzantine labyrinth of Super Metroid. However, several releases in the mid to late 90s changed the role of the narrative in games, and how they would be approached by developers, forever.

Super Metroid box art – sourced from gamefaqs.com

There were certainly games before this period that had more involved stories – for example, the Final Fantasy series, Day of the Tentacle and The Secret of Monkey Island. However, these treated the story as a separate entity – they were not necessarily integral to the design of the games. In the Final Fantasy series the story was told, through dialogues, but the gameplay was driven more through exploration and battling monsters. Likewise, in Day of the Tentacle and The Secret of Monkey Island, there were certain narrative conceits to give the characters motivations to move forward. However, the player’s motivation came from solving the games puzzles. It was later that developers began to design games where the narrative was interlinked with the games mechanics, or in some cases was the sole reason to play the game.

In 1995 Squaresoft released Chrono Trigger for the SNES. Like the Final Fantasy series, and most other Japanese RPGs that came before it, the story was told largely separate from the gameplay, through extensive sections of dialogue. However, at this time it was also the most accomplished example of player choice in a game. There were 12 possible endings, some with slight variations, leading to a different ending within the same ending. This alone was an impressive feat of game design, but, more importantly, all of the endings were influenced by the choices of the player. The narrative was an important part of the game, and the player was directly influencing the outcome.

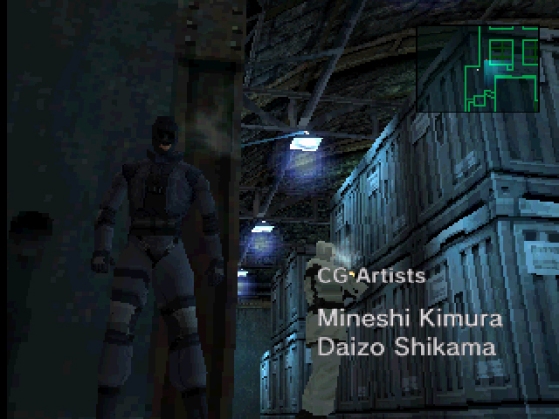

The latter half of the decade saw a different, but equally important shift in the role of game narrative, a shift that saw video gaming adopt a more cinematic approach to storytelling. In 1997 Final Fantasy VII was released, a game that did little mechanically to advance the series, but showed the most focus on story to date. There was still a very clear separation between the narrative and the gameplay. However, the story was so elaborate and involved that it sparked an emotional connection in the audience unlike any other. Many gamers cite the death of Aerith, a central and playable character, as the first time a video game made them cry. One year later, Metal Gear Solid was released – a game so focused on its cinematic presentation and philosophical soliloquy that with the story sections removed the game ran for less than 2 hours. It was cumbersome, and it more closely resembled an 80s action film rather than a video game, but it was different – it was revolutionary.

In the relatively short amount of time since the release of these iconic titles, the number of story-driven games has grown exponentially. In the last five years especially there has been a shift in the industry in regards to narrative design. There are an increasing number of games that focus so heavily on the narrative that sometimes the gameplay is entirely secondary, or loses all semblance of what gameplay ‘should’ traditionally be. It has reached a point where it is hard to pinpoint exactly what makes a video game a video game. Why do these narratives have to be told in this medium?

“Personally, and as a developer I feel like trying to define what video games are, or what anything is, is kind of a lost cause,” says Kan Gao, developer of To the Moon. “It’s almost like an act of limitation.”

To the Moon, released in 2011 by Freebird Games is a prime example of a narrative-driven video game. The story is heavily directed, limiting the player’s interactions to short sections of walking around and clicking on certain objects. It’s emotional, and very well-written. However, the gameplay certainly took a back-seat to the narrative which has seen it labelled as an ‘interactive story’ rather than a video game. Despite its apparent subversion of what a video game is, Gao insists that part of its uniqueness comes from it being a video game.

To The Moon – image sourced from steam store

“It’s a story about mementos, in both a real and metaphorical sense. And it’s something that requires the player to be mentally keeping track of so many different things – different objects and their importance and their ‘when-a-bouts’, not just whereabouts as the story progresses. And for a passive experience, like watching a film or reading a comic, it’s a lot more difficult to remember as an audience what or where or why things are. But as an active player, even if that activity is limited, such as walking around and simply spotting these objects and clicking on them gives the audience such an edge, to more deeply ingrain each of those important aspects of the game – compared to if they were just watching it.”

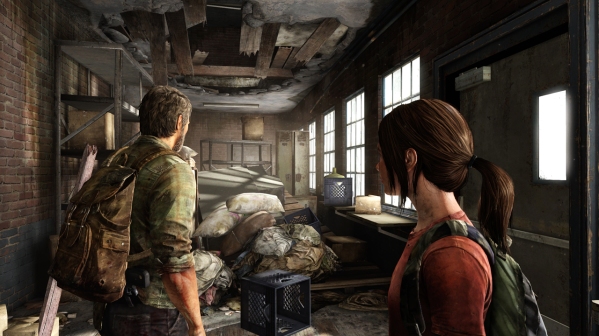

He attests to its necessity to be a video game. However, he also believes that there is something in a directed game that takes a measure of control away from the player that is antithetical to a unified, narrative focused experience. This is a problem that many mainstream attempts at story driven games face. A good example of this is Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us. In many ways it is considered a landmark in gaming narrative, telling a mature story of complex morality. However, there was also a very apparent disconnect between the story elements and the gameplay, to the extent that the gameplay was a means to deliver the narrative rather than a gratifying element in itself – it wasn’t a cohesive experience. “Developer Naughty Dog’s commitment to this dark, depressing tone is alternately impressive and frustrating. The Last of Us actively fought any enjoyment I might have gained from it — from its oppressive world to its inconsistent mechanics. Being anything but fun might be the point, but The Last of Us doesn’t always make that point gracefully,” said Polygon’s Phil Kollar in his review.

In games like The Last of Us, there is still a very distinct separation between the story and the gameplay, akin to that of precursor games from the 1990s. The themes and stories are becoming bolder and more intricate, but it is uncommon for a game to meld gameplay and story in such a way that feels unique to video games. There seems to be an intangible barrier that prevents a lot of developers from doing this. This is due to pacing. Pacing is a crucial element of telling a competent story. However, in a video game, there is no sure way to dictate the pace at which a player plays the game, other than taking some measure of control away from them and showing them the next story beat. And, for a game to tell a story unique to the medium, there must be interactivity.

The Last of Us – image sourced from thelastofus.playstationus.com

With this the question becomes have video games changed that much at all? “Yes,” says indie developer Tim Constant: “Indie Games right now are subverting our views on traditional videogame storytelling – games like The Stanley Parable and Gone Home” – games that, along with others such as Telltale’s The Walking Dead and To the Moon can be classed as ‘interactive stories’. In all of these games the level of interactivity, is limited so that the story can grow. Although, Tim insists that there is “no need for a distinction as long as there is interactivity,” regardless of how much of it there is, “it’s just another category/style of gaming”.

It seems that rather than more complicated narratives being introduced into games, the bigger change is in what defines gameplay. In Gone Home, the gameplay consists entirely of moving around an environment and examining items. There is no antagonist or ‘skill’ involved, simply exploration. Similarly, in The Walking Dead the main focus of the gameplay is making choices – choices that give the player feedback by shaping the narrative, much like Chrono Trigger did in 1995. The difference here is that the choices made in The Walking Dead change the entire game, not just the ending. Still, there is no ‘twitch’ or ‘skill-based’ gameplay involved, just decision making. Both games feature very passive, minimal amounts of interaction in order to influence the narrative – but they are interactions nonetheless.

Interacting in Gone Home – image sourced from the official website

Gaming has changed. Not just in terms of narrative, but the very notion of what a game can be is different. It’s not always perfect – sometimes the gameplay and story elements are too disparate to work together effectively, and sometimes the story overpowers the gameplay completely. It’s a time of transition, and a time of innovation in the industry, and in such a time, a perfect melding of gameplay and story seems unlikely. However, if a perfect synthesis of gameplay and story is to be achieved, the industry must be allowed to grow, free of the anchor of tradition. In the words of Kan Gao: “It’s something that has too much potential to hold on to a traditional sense of what a game should be, or is supposed to be.”